By request, I put the climate change essay on github.

github.com/worrydream/ClimateChange

github.com/worrydream/ClimateChange

(Sorry, no revision history. The revision process didn't happen inside a tiny rectangle.)

twitter.com/hypotext/statu…

Welp, looks like it's time to start studying up on non-information theory.

Welp, looks like it's time to start studying up on non-information theory.

It's easier to be a hero than to create conditions such that heroism will not be needed.

To clarify: Mead already proved scaling *could* happen physically. Moore's Law was that scaling *would* happen, in industry, at a given rate

In honor of the death of Hans Rosling (too soon), watch his video on eradicating global poverty. gapminder.org/videos/dont-pa…

Wry fatalism is the worst kind of self-fulfilling prophesy.

I looked up a mathematics term on my internet communications device.

worrydream.com/oatmeal/linear_function_of_a_vector.jpg

worrydream.com/oatmeal/linear_function_of_a_vector.jpg

Christina Engelbart @ChristinaDEI and I made a video digest of the Mother of All Demos. dougengelbart.org/firsts/1968-de…

this seemed like a good idea at the time but it just ended up depressing

twitter.com/graduatebot

twitter.com/graduatebot

1632 Galileo pretends to complain about people complaining about political suppression of earth science & scientifically-illiterate advisors

Analysis of Nonlinear Control Systems in 1964, transmitting a desperate message to machine learning engineers in 2017

Eric Betzig, recipient of 2014 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, pictured here with Windows Task Manager because PowerPoint stopped playing video.

The AI does not hate you, nor does it love you, but you are made out of attention which it can use for something else

@fnedrik: Is @ESYudkowsky's quote so famous that people know that you're paraphrasing?

@fnedrik I think writing on the internet just means assuming that for any given reference, lots of people will get it and lots of people won't.

minimum viable cathedral

@assovertkettle Holy cow, are you serious? That never occurred to me, but that must be it.

HYPERCARD! WHAT IS IT? IT'S NOT HYPER, IT'S NOT EVEN A CARD

youtube.com/watch?v=kZcEZD…

youtube.com/watch?v=kZcEZD…

bandwagon, or bandwagOFF

@noahlt: Everyone tries to defend their life choices by trying to convince you to make the same choices

@noahlt I once went to a "how to start a nonprofit" workshop where every nonprofit founder started off their session with "Don't start a nonprofit".

walked into @Dynamicland1 this morning, found a cellular automata that @qwzybug and @siglesias left on the kitchen counter last night

not gonna lie, we have a pretty nice kitchen counter

@Glench has made many wonderful things, but Laser Socks is certainly the sweatiest. glench.com/LaserSocks

When people ask what Laser Socks has to do with thinking the unthinkable, I say "Laser Socks is our Spacewar". wheels.org/spacewar/stone…

forces on phantoms @Dynamicland1

@GalaxyKate: Sounds like y'all gotta do a visit to @Dynamicland1.

I programmed a desk, a wall, a lazy susan, and a tin of paperclips.

not gonna lie, we have some pretty nice paperclip tins

@michael_nielsen:

Visiting @Dynamicland1 is like nothing else. It will become, if fully realized, a wonder of the world. A way of living in a possible future

JUST ANOTHER DAY AT THE OL' WONDER OF THE WORLD

Consider a computer which is not an "authority", synthesizing some virtual world and enforcing its rules, but rather

a "material", in the real world, which we use and shape in a physical and human context that the computer is only minimally aware of.

separated by 100 years, this is the sentence that struck me as most foreign, poignant

@qualmist:

@Dynamicland1: You Can Put Stuff In Drawers™

not gonna lie, we have some pretty nice drawers

the disruptor of all disruptors that don't disrupt themselves

When the roads aren't paved yet, you actually do want the faster horse.

"Authoring is always on." google.com/search?q=%22au…

("5 billion readers by 2017" would have sounded just as crazy 100 years ago.)

@smdnano:

Building (and re-imagining) molecular cloning tools with the

@Dynamicland1

team +

@AthenaUCSF

@DamascenoPF

@nathendel

it's just Science all the time around here @Dynamicland1

@rmozone you always come back to the classics @Dynamicland1

Lesson: expect your ideas to take hold in 100 years, and you'll never be disappointed! (from infosys.org/infosys-founda…)

I met the devil at the crossroads, and the devil gave me Linux, and I was like, come on man, I mean I get it, you're the *devil*, but seriously what is this

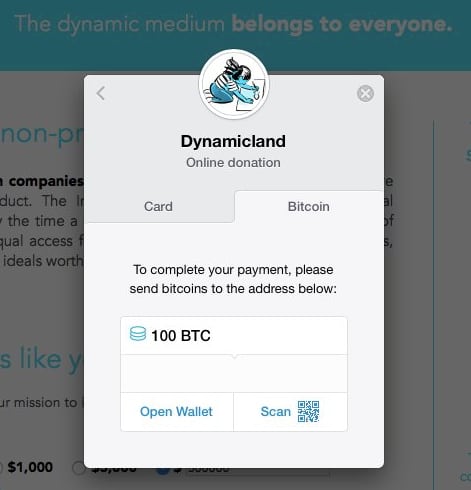

New @Dynamicland1 website coming in a few days. (I personally like the current site, but apparently it's not "responsive" on "mobile". dynamicland.org )

Hey, remember this from six years ago? worrydream.com/ABriefRantOnTh…

This fire has been burning for a long time.

I don't know what bitcoins are, but if you've got some you'd like to donate to a non-profit, we'll happily use them to build the future! dynamicland.org

(tbh I'm also pretty shaky on what exactly US dollars are... but we take those too!)

(I mean, I read the David Graeber book and everything, and that just left me even more confused.)

(Am I doing this fundraising thing right?)

(Am I doing this fundraising thing right?)

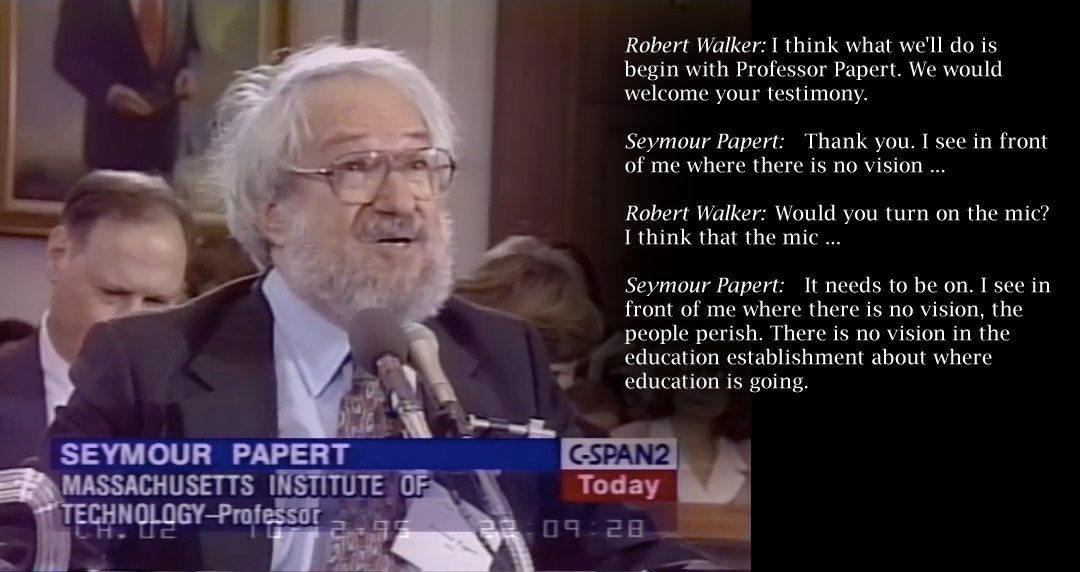

@smdiehl: Who is the equivalent of Alan Kay of our generation of programmers? Someone who has the grand unifying vision for the domain of computing.

As Kay himself has said so many times, this question is entirely about funding. With ARPA/IPTO-style funding, you get Kays (and Engelbarts, Minskys, McCarthys, Corbatós, etc) With VC and NSF, you don't.

Even Kay hasn't been able to "be Kay" since the 80s:

worrydream.com/2017-12-30-alan

Even Kay hasn't been able to "be Kay" since the 80s:

worrydream.com/2017-12-30-alan

@ciyer Alan's point is that that style of funding creates a research culture, and that culture is what's necessary. Self wasn't part of a larger movement in the way that personal computng, time-sharing, AI, and the internet were.

![Carver Mead: I always had to-especially in the early days-explain that [Moore's Law] is not a law of physics. This is a law [of] the way that humans are. In order for anything to evolve like our semiconductor technology has evolved, it takes an enormous amount of creative effort by a large number of smart people. They have to believe that effort is going to result in a successful thing or they won't put the effort in. That belief that it's possible to do this thing is what causes the thing to happen.

The Moore's Law thing is really about people's belief in the future and their willingness to put energy into causing that thing to come about. It's a marvelous statement about humanity.](media/823457072159145986-C22B1rdWQAAsNcp.jpg)

![Web browser

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A web browser (commonly referred to as a browser) is a software application for retrieving, presenting and traversing information resources on the World Wide Web. An information resource is identified by a Uniform Resource Identifier (URI/URL) that may be a web page, image, video or other piece of content. [1]

Chromium is 25294722 lines of code.

25,294,722](media/857794605076500480-C-d_pEAVoAAVcmB.jpg)