RAND Corporation Report No. P-847, April 20, 1956.

Published in Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 3, Special Issue on the Administration of Research (Dec., 1956), pp. 326–339.

The authors discuss some organizational problems of the new research corporation from the point of view of an administrator and a researcher. A tool for improving communication between them is described, and its use in planning a large-scale research program is outlined. G. H. Putt is research administrator and J. L. Kennedy is head of the Psychology Research Department at The RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, California, a nonprofit organization engaged in research for the United States Air Force and Atomic Energy Commission.

This paper is the result of an attempt to pool the experiences and attitudes of a research administrator and those of a researcher in order to describe some frequently encountered administrative problems of the new ”research corporation” and to suggest a way of alleviating one of these problems, namely, communication between research administrators and researchers.

Although little general agreement exists as to what kinds of human behavior constitute research, a great deal of it is being done and a substantial amount of money is being spent in support of it. In some quarters, research is practically equated to living, in the sense that all living organisms must conduct investigations on the physical environment and on the behavior of other living organisms in order to stay alive. The purpose of such investigations is to predict and, by one’s own behavior, to control the physical and cultural environments. In this sense, every living organism is a researcher and, specifically, all human behavior is research.

Mankind’s development of science and the scientific method, however, have created a set of descriptive categories with which we now like to think about research. We have observed over the ages that a few people are driven to ask questions of nature or of the behavior of other living organisms that go far beyond the kind of observations that other people make in the normal course of living. We call this kind of behavior “basic” research as opposed to “applied” research. Applied research recognizes the constraint of time or timeliness for the solution of a current problem, while basic research is relatively timeless. Both formal varieties of research require design and application of special tools or methods in specialized institutions such as libraries, laboratories, universities, institutes, and corporations. The research corporation is one of the most recent institutional innovations. Because it is new and relatively untried as an institution, the research corporation way of institutionalizing the research function is of particular interest and should be the subject of study in its own right, even though we have relatively few examples to investigate.

Why do we now have research corporations? What are the motivations of people who are willing to work in an untried institutional format? What kinds of people now work in such an environment? Where do they come from and where do they go? What do they produce and how can they be administered to produce most effectively? Are the problems of administering a research corporation different in any way from those of administering a university, a large business, or a research laboratory? These are questions on which little quantitative information is available. In order to study them, one conducts research of the more primitive type, with the primary tool of participant observation.

It seems to us that research corporations may have emerged for two interrelated reasons: (a) It is possible that research in the universities and industrial laboratories has become narrowly specialized and increasingly out of touch with the larger needs of society for solution of the complex managerial problems produced by the rapid growth of technology since World War II. (b) It may be that a new willingness has emerged to try the methods of science and technology in areas heretofore considered to be in the realm of the executive, the manager, and the policy maker.

A trend toward specialization of output almost inevitably produces a counterreaction to find a mechanism for integration. So the research corporation appears to be a reaction to overspecialization. If it is true that the research corporation is a mechanism for integration of diverse specialized knowledge, one may ask what unusual techniques it has developed to perform this function. One answer seems to be the emergence of the interdisciplinary research team, or at least of an attempt to pool or mass brain power from a variety of traditional disciplines. It is here that the administrator of the new research corporation encounters his most difficult problems. Here lies the uniqueness of the research corporation when compared with the university, the industrial or government research laboratory, or the research institute.

The interdisciplinary-team solution to the cry for integration seems simple and straightforward on the surface, but in it is a Pandora’s box of unsolved administrative problems involving human motivations, traditions, habits, expectations—in a word, culture. Every new organizational form runs up against cultural lags, deep-seated traditions, and well-entrenched conservatism. The research administrator who embarks on a research venture involving the interdisciplinary team should weigh carefully the cultural costs of integration. This paper will attempt to describe some of the problems associated with the interdisciplinary solution. It will also describe a tool or method that the authors believe will assist interdisciplinary teams in carrying out the integrative function and will improve communication between administrators and administered.

One of the first observations to be made about the various separate disciplines of science and technology is that each has built up its own framework or culture represented by preferred ways of looking at the world, preferred methodology and preferred terminology, preferred ways of presenting results, and preferred ways of acting. These preferences run deep—they are inculcated as possibly the most important aspect of undergraduate and graduate training. To be an engineer is not only a matter of learning some substance and some methodology but also a matter of learning to prefer certain kinds of information about the world and to prefer certain methods for utilizing this information. A study of the transmission of the culture that defines the words engineer, physicist, sociologist, and mathematician is really a study of the history of science and technology. The “natural philosopher,” when science was new, was the “generalist”—a whole interdisciplinary team wrapped up in a single nervous system. Benjamin Franklin was at least a physicist, a philospher, an engineer, and a diplomat. The natural philosophers were men unhampered by the accumulated culture of science. They built their own frameworks for understanding the world. They were primarily engaged in “search” as opposed to research. They developed ways of discovering how to think about problems as opposed to getting answers to questions posed within an established or traditional framework. Searching appears to be the traditional function of the philosopher. With the sharp line drawn in modern times between philosophy and science, searching for the better framework in science seems to be confined to the very few philosophers of science and technology—the many do research.

Research has come to be as ritualistic as the worship of a primitive tribe, and each established discipline has its own ritual. As long as the administrator operates within the rituals of the various disciplines, he is relatively safe. But let him challenge the adequacy of ritualistic behavior and he is in hot water with everyone.

The first conviction of the research specialist is that a problem can be factored in such a way that his particular specialty is the only important aspect. If he has difficulty in making this assumption, he will try to redefine the problem in such a way that he can stay within the boundaries of his ritual. If all else fails, he will argue that the problem is not “appropriate.” Research specialists, like all other living organisms, will go to great lengths to maintain a comfortable position. Having invested much time and energy in becoming specialists in a given methodology, they can be expected to resist efforts to expand the boundaries of the methodology or to warp the methodology into an unfamiliar framework.

Thus an unsolved problem for the administrator of research in a research corporation is how to induce the members of his interdisciplinary teams to indulge in search for the adequate framework rather than research. Research tends to yield a set of unintegrated answers on components of the problem. The integration demanded by the problem must then be done by research administrators and directors, using the best framework available—usually the administrator’s own private framework. Again, no one is satisfied. The administrator is unhappy because he usually recognizes that his framework is not the best possible one—and the research specialists are unhappy because their individual contributions are often distorted and unrecognizable. Frameworks are most difficult to communicate because one quickly runs into fundamental philosophical and cultural issues.

The fact that individual contributions tend to be distorted or to disappear in a larger framework also is an unsolved problem for the administrator. Our research culture is based upon reward to the individual, not to the team. The perceptive research specialist knows this fact of life perfectly well; hence the interdisciplinary team is unstable on at least two counts: the sweat, blood, and tears of trying to resolve conflicting values and the problem of reward to individual members. The appropriate expectation for interdisciplinary teams appears to be that they will be unstable associations. But it is precisely interdisciplinary search behavior that the research corporation administrator needs and should insist upon. Research can be done by the individual specialist, once the framework has been established, although certain large problems will require continued close cooperation during the research and development phases.

Development, the process of putting research results into practice, also requires a framework, but here the problem is not search or research but the acceptance of a framework established by search and research. The research specialist who enters the field of development should recognize the existence of a framework and expect to behave in accordance with it, to be constrained by it, and be required to support it. The argument that search and research specialists should not enter the development field because of these constraints is rather attractive in the abstract, but the individual rewards for doing so will continue to attract search and research-oriented people. The problem for the development administrator is to communicate the framework effectively and to insist upon at least a minimum acceptance. When development programs regress to a basal stage in which the framework obtained from search and research is continually under scrutiny, little development work gets done.

We have now established the need for a search procedure, device, or method which will perform the following functions:

(1) Provide a framework within which research administrators and research specialists may interact and make decisions about what research should be performed and how research should be carried out in order to answer the large, complex, interdisciplinary problems of “real life.”

(2) Provide a framework for effective communication with persons engaged in development. The primary problem that such a tool should help to solve is that of communication between research administrator and researcher and between researcher and developer.

As a participant observer in two major interdisciplinary-team efforts over the past five years, one of the writers is now quite familiar with two rather different approaches to the interdisciplinary problem.

The first approach may be described as the “brute force” or “common enemy” technique, in which the interdisciplinary team picks a relatively unexplored area, such as organizational behavior, for its activities and “lets the problem be the boss.” Thus in the first of the above-mentioned team efforts the scientific framework was postponed, and decisions were coerced by choosing first to put a large, interacting man-machine system into a laboratory so that it could be thoroughly observed. The scientific framework or model emerged after the experiments had been completed. The observations carried out in the laboratory were made for the purpose of establishing a framework, which then made possible decisions regarding what research should be conducted and how it should be conducted. This team, then, set out to observe a complex phenomenon in ways that would lead to a scientific framework.

The serious administrative problem with search activities carried on in this way is that the team may be apparently unproductive for a long time. Unless the research administrator completely understands that search rather than research is going on, he will tend to apply inappropriate criteria to the work. The obvious solution to this communication problem appears to be to include membership from research administration on the search team in such a way that the uncertainties, communication problems, and value impasses may be directly experienced and progress assessed

From the administrator’s point of view, much of searching is not publishable in standard research journals, nor is it of great interest to those not engaged in the process. It is tentative, rapidly changing, full of sudden insights and long fallow periods, unpredictable, and unpopular with colleagues engaged in exploiting more traditional frameworks by more traditional techniques. But search is the lifeblood of a research corporation, because new tools come from new frameworks. Specifically, the new tools for the solution of complex system problems will come from the searching of interdisciplinary teams if we can find a way to stimulate and reinforce the team concept.

The second interdisciplinary team had a quite different way of operating. Here the time and facilities were sharply limited and the interdisciplinary framework was the initial focus of attention. The team was fortunate in discovering a problem on which previous observation and research had already accumulated much factual information. The problem of this interdisciplinary team was to try to fit the information together into a coherent context from which decisions for future research could be made. It attempted to solve the interdisciplinary communication problem by constructing a “contextual map.” Before discussing the map we shall first give some indication of the team’s problem.

During a recent leave of absence which was spent at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, Kennedy worked closely for a year with a political scientist (Harold D. Lasswell of the Yale Law School), an economist (C. E. Lindblom, Department of Economics, Yale University), and an anthropologist (Allan Holmberg, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Cornell University). The problem—chosen because of its ramifications in anthropology, economics, political science, and psychology—was to plan a ten-year program of rapid cultural and technological change in an underdeveloped region.

The region was an inter-Andean valley, the Callejón de Huylas, in north-central Peru, where Holmberg, the anthropologist, had been operating the Hacienda Vicos, rented by Cornell University from the Peruvian government, as a laboratory for the study of cultural change.

Hacienda Vicos is on the western slope of the Cordillera Blanca (the “White Andes”) at an altitude of about 9,000 feet. The land, which is some 22,000 acres in extent, ranges from a few acres of rather fertile river bottom through arable uplands to many acres of high mountain land suitable only for grazing. About 2,500 Indians live on the hacienda. They own none of the land, but work it for the hacienda management and their own subsistence. By long-standing custom, Indian families provide the work of one member three days a week to the hacienda management in return for the right to use some of the land. The land is thus parceled out between the hacienda management and the Indians. Because of this way of renting the land, managements come and go, but the Indians remain on the land, living out their life cycle in almost complete isolation from modern coastal Peru and the outside world.

The Indians, the land, and the hacienda management make the region a complex interacting cultural system into which the Peruvian government, Peruvian entrepreneurs, and outside capital are introducing modern technology. For example, a large hydroelectric project being built some fifty miles from the hacienda with French capital is expected to provide electricity for the whole Callejón de Huylas within a few years. Roads are being improved, trucks are coming into the valley, and communications are being established with the coast.

The Peruvian government recognizes that the hacienda, an anachronism in the modern world, must go. But what will replace it?

The Indians who constitute about 70 per cent of the population of Peru, are not ready for modern technology—either culturally or politically. To avoid the extremes of revolution on the one hand and race extinction on the other, plans were made to carry the Indians of Hacienda Vicos from feudalism to political and cultural participation in modern Peruvian life in the relatively short time of ten years. To do this, planned experiences, or “interventions,” were started in 1951. These interventions are the independent variables of this experiment in cultural change; the resulting changes in behavior are the dependent variables.

The interdisciplinary team which we have just discussed was faced with the complexities of a large interacting cultural system and its own problems of internal communication. A method was needed for systematically utilizing the talents of the team members despite the frustrations of having to establish a common vocabulary, an agreed-upon ideology, a set of reasonable goals, a common context for symbols, and ways of translating ideas into actions. The solution hit upon was to design and make up a “map room,” whose walls contained a large matrix with the time (in years) on the ordinate and with the “variables” the group was interested in along the abscissa. This matrix was the “contextual map.”

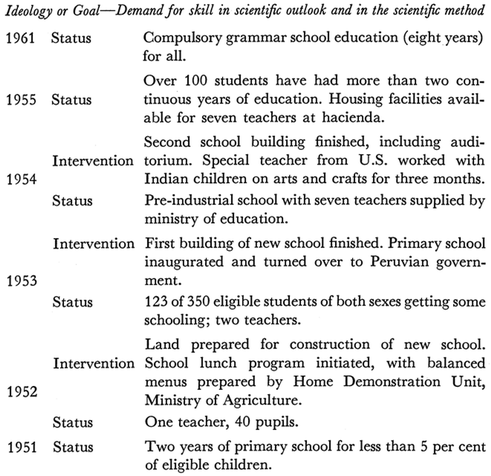

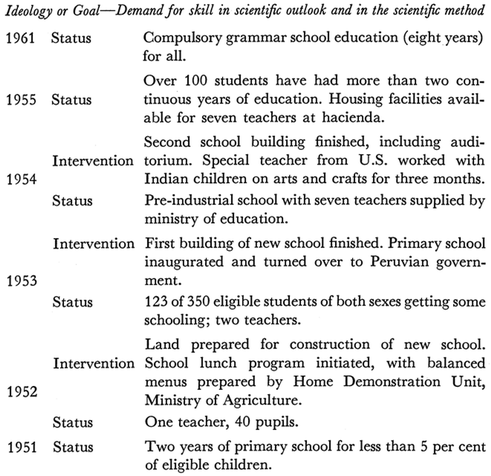

Since the team began with some 250 variables, room space was soon exhausted. The map that was finally used had 130 variables, grouped under “government,” “economics,” “social relations,” “education and mass media,” “health and welfare,” and “attitudes.” There were spaces for three-by-five cards for each of ten years under each variable. The entire matrix thus could hold 1,300 cards that summarized the value of the variable in the past or described its desired value for the future. At the top of each column was a description of the value of the variable “in the best of all possible worlds” and a statement of the value anticipated or desired at the end of the ten-year experimental period (1951–1961).

Since the group was working in 1954–1955, and the ten-year map extended back to 1951, it was necessary to work back to the bottom of the map. From a thorough base-line study of the community, an estimate of the 1951 value of each variable was obtained and, from a second study, descriptions of past interventions and values of the variables were established. These were placed in the proper time sequence. As an example, the column for the variable “number of required school years” under the group heading “education and mass media” looked like this:

One of the main difficulties in programming and planning is the need to deal with large numbers of interacting variables. Programs of any degree of complexity strain human memory. The contextual map records past decisions and actions as well as predictions and anticipated reactions for the future. The map is a way of keeping “minutes” in a context of the past so that the relevance of decisions is immediately apparent Each member of the group can refresh his memory for a meeting by “reading” the minutes in this context.

The map room contained a conference table and chairs so that decision-making and planning conferences could be held there. Thus the group was continually confronted with the developing map and the members were constantly aware of gaps in the information and suggested priorities for items to be considered.

The map was a large, living memory for the group. As the decision-making conferences went on, each member of the group begin writing three-by-five cards and coding them for their proper place on the map—a letter and number on the original card told the secretary where to post the duplicate card she typed up. By the next meeting, the cards would be posted and the members of the group could refresh their memories of previous discussions by referring to the map.

A common characteristic of planning and decision making is the lack of a tangible product. There is little motivation for people to take part in these activities because they get so little reinforcement. Using a contextual map gives two kinds of reinforcement. There is a “product”—the developments on the map—and a prediction reinforcement. The prediction reinforcement takes place over a period of time, since the map continuously compares the predicted status of the variables with their actual status. Systematic comparisons of predictions with the actual events make it possible to improve the prediction methods used by the group.

One of the best features of this kind of display is the ease of duplicating it. The position coding of the cards makes it possible to put up duplicate maps in many places at once—and this can be done with the whole map or with pertinent sections of it. The cards can easily be carried or mailed in a small card file and set up in a new matrix in a short time. For example, the map used at the Center was set up for the field staff of the project at Hacienda Vicos in about half a day.

Because of its portability and ease of duplication, the contextual map is a useful briefing device. At the Center it was found possible to get the essential nature of the project across by taking new people into the map room for a briefing and allowing them to wander through the project by reading the cards. The map could even be photographed and made into slides that could be projected on a screen during a briefing.

The map room is, in one sense, a “learning machine.” The parts of the machine that do the thinking and adapting involved in learning are, of course, men—the planners. But they are aided by a display that responds to the issues before it by making the complete context of the decisions readily available and by quickly assimilating current information, decisions, and predictions.

There is nothing magical about this technique. Man, as always, solves the problems. But man’s talent for planning can be greatly increased if he has better tools to work with—if the men who make the plans are given ways of combining ideas into understandable formulations they can employ systematically.

Having said this, we can point out the unsolved problems in this method of planning. Since this technique, like any other, is only as good as the ideas that go into it, the best information must be made available and competent talent must be employed. Men with relevant experience and appropriate talent need to explore the domain of the project step-by-step and lay out the problem in several dimensions—in the Hacienda Vicos example given above these dimensions were time and cultural conditions. This requires improvement in internal communications—a difficult problem in most planning projects but one in which the map technique may prove useful. If the problem is approached in this way, immediate questions and appropriate “interventions” can be identified and acted on, and decisions can be recorded so that their consequences can be checked in the future.

Further technical development of the map is necessary, of course. A more effective way of storing, manipulating, and displaying large quantities of information about goals, predictions, and past, present, and future conditions is needed. For this we can look to high-speed data-handling equipment and the many recent developments in displaying information electronically. An ideal map, for example, might give the decision-making group a listing of all relevant variables, in order of priority, before each decision.

The design of the map room itself is a fascinating problem. Obviously the size of the room should not limit the extent of the map. What seems to be needed is a large room that can be made into different-sized smaller rooms with theater flats and temporary partitions. With the proper use of space many decision-making groups should be able to use a number of maps simultaneously in the same general area.

The contextual-map method is obviously still in a low state of development. But because of its facility for display, communication, memory, and reinforcement, it promises distinct and unique advantages in formulating, monitoring, and managing interdisciplinary search programs.

Finally, the contextual map should not be confused with the scheduling boards commonly used in the control of development programs or in the control of industrial processes. The contextual map is a technique for finding a framework. The scheduling board is a way of exploiting a framework. Both techniques use large displays and may exhibit time as one of the axes of the matrix, so that, in end product, they may look quite similar. But the contextual map attempts to organize information into new and more meaningful categories, whereas the schedule board merely exhibits the consequences of adopting a framework.

The research administrator may now ask, “Which of these modes of operation is preferable, framework first and then research, or search-framework-research?” The answer seems to be that such decisions depend upon many factors. It should be noted that the Peru group was completely dependent on five years of field observation and investigation for the information about the context of Hacienda Vicos it used in constructing a contextual map. The organizational-behavior team also required a large investment of time, money, and energy to collect the information it needed to proceed with the construction of a theoretical model.

No amount of administrative wishing will circumvent the requirement for the collection of much information about complex problems before the new framework can emerge. Individual administrative preference is about the only tool that can be applied to the decision as to how the experience should be gained—whether in direct contact with the phenomenon in laboratory and field installations or through the secondary sources of the study of documents, journals, histories, and other compilations of accumulated wisdom.

The research administrator can insist, however, that interdisciplinary searching be carried out in a communicable, systematic manner and that it have a product, such as the contextual map. He will improve communication between administrator and the search team by finding ways of “joining the team,” thus injecting his attitudes, information, and values into the interdisciplinary product, a framework within which specialized research can proceed with some confidence that the results will at least be relevant to the problem.